Why the Next Socialist Revolution Will Be AI-Led

The Socialist Dream Is Alive in the Age of Data

Socialism, wherever it takes root, begins with a single assumption: equality means identical outcomes. If one citizen longs to eat the same dish, wear the same coat, or live in the same neighborhood as another and cannot, the system cries "unfair." To correct the imbalance, an enlightened, ahem, group of humans seizes the factories, fields, freight lines, and anything that someone could want for themselves and then issues its verdict on what everyone "should" receive. If the decree is one pound of protein daily, the 120-kilogram weight-lifter and the 40-kilogram ballerina each collect precisely one pound. No more, no less. Any variance, the planners warn, is favoritism, and favoritism is injustice.

History shows how badly that wager on omniscience performs, yet the impulse never dies. It returns in new costumes. In the middle of the 21st century, I believe the costume will be digital. As AI systems grow more personalized, more predictive, and more deeply wired into the guts of states and corporations, at least one ambitious politician will start to believe the AI models truly see the nation's needs. This belief could lead to implementing what I term 'AI-based central planning'—a system where decisions are made not by human commissars, but by AI systems, with only screens glowing green. The interface will feel humane, even bespoke. But the substance will be the same: choice smothered, incentives mangled, harm disguised as help.

I'm the first to be surprised by how pessimistic I sound. One more economist overdosing on worst-case scenarios. Yet I spend my days steering algorithms and have seen their reach. A twenty-dollar ChatGPT subscription already guesses the dog breed I’ll buy, the conciliatory line I’ll offer a client, the instrument I daydream about playing—none of which I ever typed into a prompt. This is a single model making these guesses. As models interact with each other, their ability to make accurate guesses about who I am will only increase, and, with this improvement, the perception that one could ever predict everyone’s needs will enter someone’s head.

Here's how I see the creation of AI-based central planning happening:

People have unstable desires. You want pizza today and pancakes tomorrow. A frozen list of preferences can prevent you from getting what you really want.

One-brain plans crack. Socialism bet one mind can freeze every taste. But no mind of flesh or circuits keeps up with shifting cravings.

AI seems to be the answer. Dashboards vow to log every click and craving, then compute the "perfect" plan in milliseconds. Leaders imagine a world finally tamed by data.

Solo AI gets smarter. ChatGPT nails your dinner, and streaming services learn your song habits. Each correct guess tightens our loyalty to the tool and the perception that it knows us better than anybody else.

Models share their data. OpenAI feeds Azure logs; Claude feeds ChatGPT prompts; your exercise app feeds Google Fit. Google Maps knows I'm not around the corner, as I told my friend, but in the shower.

States see the value of data. Health records go to pharma; transit cards feed social-credit scores. Governments barter dossiers, opening the windows on your life.

AI models co-evolve. Even no-code tools stack research engines, spreadsheets, and image generators in seconds. Model-to-model handoffs occur in milliseconds worldwide.

Data becomes capital. The larger the pool, the cheaper each prediction and the harder it is to rival. Siloed models merge into one all-seeing reservoir, begging, "Can we allocate resources better than selfish humans ever could?

What if, rather than predicting which Harry Potter house someone should attend, a state uses AI to predict the neighborhood that’s right for them to live in, based on millions of data points? What if that question is asked about the job you must accept, the clothes you may wear, and the meals you may eat? It seems only delusional until we remember that socialist states have mandated all of this before, but now they could do so with the added confidence of “proper” prediction.

I. Why No System Can Fully Know What People Want

Economics can never fully predict human behavior. And because it can't, it can never function as a science. Not in the way physics does, where outcomes follow laws with reliable precision. This isn't a failure of economists' ingenuity; it's baked into the subject. Human preferences shift constantly. They are nudged by mood, shaped by culture, rewritten by technology, or upended by sudden shocks.

Even if I detailed every intention for tomorrow in my calendar, no model could confidently predict what I'll think, want, or do. Our desires evolve faster than our theories. Our theories can't even explain our oldest desires. And for that reason, economics will always stall at the edge of the individual.

Ask twenty-five-year-olds what they want tomorrow. They shout, Pizza! So you order fifty pizzas. Dawn breaks; a cartoon hero flips a pancake on TV. Suddenly, half the class chants, Flapjacks! Your airtight plan springs a leak in twelve sleepy hours. Adults? We're taller but just as fickle.

Yet for all the unpredictability of what humans want to consume, markets flow. The genius of free market economies lies not in eliminating uncertainty but in distributing it by allowing people to act, react, and self-correct. This adaptability is a testament to the resilience of free markets in the face of human unpredictability.

Take prices, for example. In Mexico City's wholesale avocado market, the price of Hass avocados from Michoacán might spike 34 percent overnight. No one needs to know why. What matters is that the spike occurred, and the moment it does, decisions begin.

Distributors hundreds of kilometers away might assume a hailstorm hit the orchards, fuel prices rose, or foreign buyers drove up demand. It doesn't matter if they're right. What matters is that prices are up, and they need to do something about it. Warehouse managers might reroute shipments. Sellers might substitute frozen pulp. I might find mangos instead of avocados at the Tuesday farmer's market. No one explains. The farmer says, "Avocados are expensive, bro." I say, "damn," and buy one less avocado. Everyone adjusts.

Zoom out from this one case—multiply it by hundreds of thousands of products, across millions of individuals—and you begin to see how free markets work. People want things. They act on those wants. The system responds.

But substitute that organic messiness with a central plan. Let some authority decide what people should want, how much they should consume, and what it should cost, and you get repeated, predictable failure.

Watching that messy bazaar, some officials will mutter. If only we could pause the picture and know every price and craving, then we'd hand out goods perfectly. A kind impulse, on paper. Yet pausing a river with your palm brings one result: water backs up, and banks burst elsewhere.

Rent control is a prime example. When cities freeze rents below what people would naturally pay, landlords respond by cutting maintenance, converting units into condos, or turning to Airbnb. The apartment might have one of these toilets that can only flush once every 20 minutes, but why would the landlord renovate it if they get the same money? Let them wait. So what happens is that tenants pay less in cash and can't pee too frequently, and now they live in crumbling buildings or, worse, can't find housing at all because landlords might prefer to keep the apartment for themselves now that they can't earn the market value of the property. The policy, meant to equalize outcomes, punishes the people it claims to protect.

Consider public healthcare to further understand the mess that deciding "what's right" to happen in an economy causes. When states set fixed fees, doctors chase the procedures that pay the most, like advanced imaging, and neglect primary care, which might pay far less. If a doctor earns the same amount of money no matter how much effort they spend, why do more? Patients become interchangeable. Either the state will keep sending new ones, or the old ones will have to be returned because they don't have an option. Because they can't go elsewhere, the healthcare systems don't have competitive pressure to improve.

In both cases—landlords letting buildings rot and doctors ignoring what helps most—the problem is not malicious intent. It's warped incentives. Remove the link between effort and reward, and people do what's easiest, what's asked of them, or what the state literally says they can do (and no more), not what's best.

Markets are messy precisely because human life is messy. However, the price mechanism, albeit flawed and fragile, and one of many others, remains one of the best free market tools we have ever had to coordinate diverse, unpredictable, and evolving human needs. Distort or silence it, and the mess doesn't vanish. It just becomes harder to see. It then BOOMs somewhere else, often causing far greater harm.

My prediction, which this section made crucial, is that some country will eventually claim that artificial intelligence will perfect allocation. Remember, though, the obstacle has never been computational horsepower but the audacity to believe human wants can be frozen long enough to calculate.

II. Why Governments Keep Pretending They Do

Every time a government has tried to guarantee equal results by predicting what people "really need," the pattern is the same: human variety is misread, life's essentials misallocated, and, despite noble intentions, misery follows.

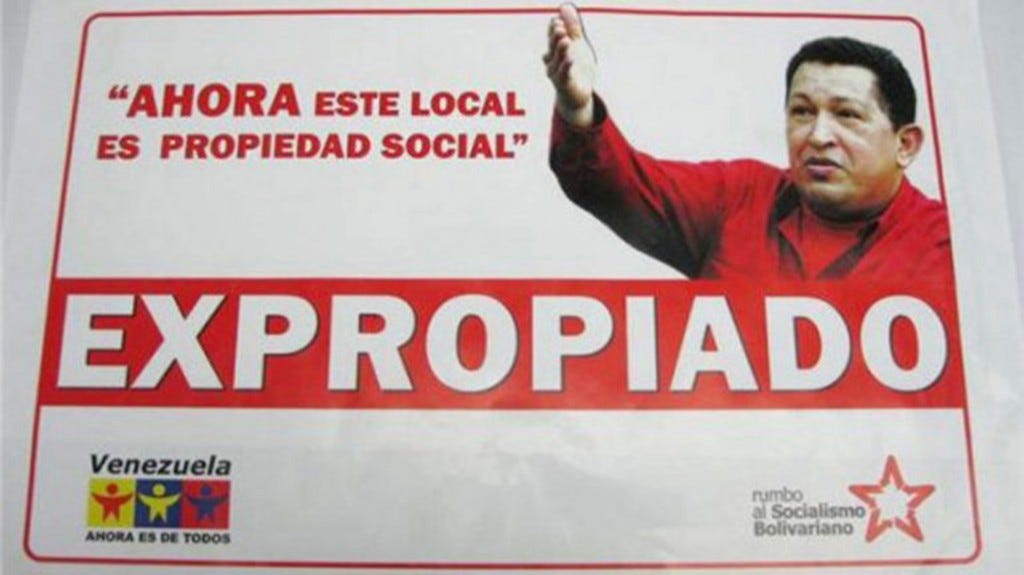

In the Soviet Union, millions were arrested because the state said that millions had to be arrested. In Chávez's Venezuela, 28,000 acres of farmland were seized "for social need," with thousands of families becoming homeless. From 1958 to 1962, Mao's Great Leap Forward pulled up to 90 million peasants out of the fields and into backyard steel furnaces, which produced nothing but useless pig iron. Grain output collapsed. A famine followed, claiming 30 million lives.

And those are just the high-profile cases. There are countless quieter examples. In cases where states forced couples to separate because singles might feel it's "unfair" to live alone, or the 300 grams of daily protein, going from counting the meat alone to also counting the bones. Jobs were assigned by lottery: citizens reached into bags filled with slips of paper, each labeled with a task that "needed to be done." The list goes on. Ask an AI about them.

If socialism's failures are this stark, why does the idea survive?

There are many reasons, but a central one is that socialists can't accept that it's ok for humans to live different lives.

Every human is different—height, culture, beliefs, tone of voice, taste in partners.

Every human is rarely satisfied with what they have.

And there is always someone who has something you don't.

Free-market societies like the U.S. acknowledge this and say, fine; let's give everyone a chance to change their condition through effort. Socialism, by contrast, appeals to desires and resentment: if your neighbor has more, it must be someone else's fault, NOT YOURS, and the state must fix it, not by opening the field to new players, but by redistributing the scoreboard.

After centuries of moving away from Aristotle's vision of the virtuous citizen and toward doctrines that humans must be increasingly controlled (Hobbes, Aquinas, Machiavelli, etc.), Marx's early manuscripts felt like a return to humanity. It said, "YOU mean something." This philosophy resonated back then and still does with most who feel oppressed.

That resonance convinces me that socialism will return. U.S.-sized, institutional, but this time AI-powered. I cannot envision a future in which no one suggests that the real problem was our inability to know what everyone wants or how goods and services are allocated. And who won't be tempted to try again as AI begins making decisions in real time and reporting back on data?

Once that belief takes hold, all those past failures—Stalin, Mao, Chávez—will be dismissed with a single phrase: "We've never tried it with AI."

So far, we've learned two things: no one can predict everyone's wants, yet governments keep pretending they can. Enter AI, the shiny new crystal ball. Its boosters will say, "Sure, humans blew it, but the machine has data." Picture a stage conjurer yanking the same rabbit from the same hat, vowing the next pull will reveal a dove, because he's wearing smart glasses. AI is the smart glasses: dazzling tech over the old trick.

III. Why AI Will Tempt Them to Try Again

The dream of a single intelligence—a bureaucracy, a corporate dashboard, or an autonomous agent—rests on two ancient longings: we crave certainty and trust that our private quirks can be decoded. Economics, psychology, neuroscience—all the soft sciences flirt with that hope. What's new is that, with data, this might seem possible.

Ten years ago, political marketers could already "seed doubt" about someone's beliefs with one ad, introduce an alternative story with the next, and then nudge voters. The Cambridge Analytica scandal was the first headline case, but I watch the same mechanics running ads for companies daily. In less than an hour, I can pay Facebook to show a specific set of messages to 40-year-old white men who make more than six figures a month and like basketball and Barbies. Not only can Facebook find this person in seconds, but it can also, without my intervention, change how the ad looks and sounds, and what it says, in a way it has automatically determined the viewer will like. We like to tell ourselves the feed doesn't shape us and that we spend three hours daily on TikTok because we willingly want to do it, but the revenue charts say otherwise.

Algorithms can't always serve the exact information that will make someone stay on a platform, and ChatGPT can't always guess what I would like for dinner, but—literally day by day—they are perceived as more capable of doing so. Now link the increased perception of LLMs knowing us to three short-range trends:

Data pools are merging. Microsoft's exclusive OpenAI deal pipes every model upgrade into Azure, and Azure logs flow back for tuning. I can already build workflows where ChatGPT and Claude share real-time notes.

States are buying and selling data. Israel's vaccines-for-data pact gave Pfizer real-time health records. Britain handed Palantir the NHS spine. China weaves tax returns, subway taps, and court rulings into a national Social-Credit web.

The lines between tools are evaporating. Gumloop, a no-code tool for building AI-based workflows, lets a midsize firm fuse Perplexity research, Google-Sheet logs, ChatGPT tags, and DALL-E graphics in seconds. Meta's Advantage+ edits videos mid-flight for micro-audiences. Model-to-model handoffs now happen in milliseconds at a global scale.

Add the economic logic: data behaves like capital. The bigger the trove, the cheaper each marginal prediction and the fatter the moat around future profits. Today, OpenAI and Anthropic hoard their own sets; tomorrow, why not a single reservoir, sold wholesale to every connected device and fed back into the models?

Technologists (driven by ego) and entrepreneurs (driven by profit) like to say, "none of this has happened or can happen!" There are many childish insults I could write to them, but what I'll highlight, as an adult, is that they are missing the governing distinction of the system in which AI is slowly operating. Complicated systems, like circuit boards, yield to mastery; complex and complex-adaptive systems—populations, markets, minds—do not. Current computers obey; human desire mutates. But this can change next year. Large language models now sit at the hinge: they began as complicated stacks of linear algebra, but as soon as they are networked together—which could happen at any moment, because each company's LLM works better with others (a company incentive and a human incentive)—we could see AIs feeding on fresh data and fine-tuning one another. They are fast becoming complex, even co-evolving. Language links human minds (and soon machine minds) like Ethernet cables strung between skulls, creating feedback loops whose emergent behaviors we cannot yet name.

Yet while the naïve technologist and entrepreneur shower us with arguments like "AIs aren't mean because we didn't make them mean," the socialist's fantasy comes true. A dashboard asks, What will Nicolás eat next month on his mandated $50 budget? and spits out ration credits. Lonely singles are slotted into co-living pods; perhaps I'm shipped to a Vietnamese island because my "open" personality profile balances two highly neurotic introverts. My new occupation? Cook, though I've never sautéed an onion. If the model flags me as "net negative," it can either inform a human that I need to be murdered or, more efficiently, connect to whatever physical technologies we will have in the next five years—technologies tied to LLMs—so that the AI itself can eradicate me and my incredible dance moves from existence.

Pieces of this future already exist: $40k-a-year schools where teachers "coach" while AIs define what each child needs; loan rates set by shopping histories; chatbots that describe "who you are" better than your spouse. Stitch the pieces together, think further about what an AI could comfortably predict about each of us if it had enough context, and we will revive the socialist flame under the banner, We can finally predict!

And yet the algorithm will still break because tomorrow I will want something it never logged because even I didn’t know I would want it. Same mass suffering, same disregard for people’s individuality, but this time, visualized on a minimalist software dashboard.

No model, however clever, can ration a soul. But someone will believe it can, and that’s what we should all worry about.