More Kids Are Learning by Doing—But at What Moral Cost?

Losing the ‘How’ in the Pursuit of the ‘What’

I.

Many alternative education schools offer creative, project-based learning. These schools encourage students to launch social media brands, write books, or start small businesses. At first glance, they promise environments, peer networks, and curricula that help students attach meaning to what they learn.

Yet, do these schools focus so much on the end goal that they ignore how students get there? When communications highlight only a specific financial target or a socially prestigious achievement, is the process—the “how”—lost? Do we even lose anything if we lose the how?

Although I am not a student in these programs, I can draw lessons from adult environments that chase financial success or social prestige without moral reflection or self-examination. People reach their goals in these environments, but their methods can harm themselves, their colleagues, or society.

An ambitious person with a “winner takes all” mindset is a clear example. Only the result matters. Think of Adam Neumann, who made WeWork seem endlessly successful; Martin Shkreli, who raised an HIV drug’s price by 4,000%; or Donald Trump, who urged his followers to “attack, attack, attack” while “denying everything.”

Indeed, these founders and executives thrive in an environment that applauds and supports achieving the thing. However, devoid of any regard for values, morals, or others, support is conditional. It’s a culture fueled by the belief that for me to win, you must also win—but only insofar as your winning furthers my agenda. Should we be surprised if alternative schools, by highlighting an educational environment focused on achieving the thing and not on how it is completed, would form values that better serve achieving outcomes, just like any other environment influences the formation of values nurtured within that environment?

I spent six years in the tech industry, receiving generous help from founders and investors eager to see me succeed and achieve my goals. Yet I also saw that help vanish quickly when I was no longer helpful for them to achieve their goals. Lose a key client, refuse a favored hire, or forget to introduce them to someone, and support evaporates overnight.

Some argue that in a results-driven world, ending relationships is simply the cost of doing business when they are no longer helpful. But could promoting this mindset, either by direct amplification or by the non-promotion of different environments, affect children who attend these agency and project-driven alternative schools? Could we expect kids to develop them in these environments despite most adults in similar environments not doing it? Given that these schools are new businesses that haven't graduated many students who are now adults, we can't say for sure. However, looking at the people "created" in similar environments, we should at least worry about who's coming to the other side of these programs.

II.

Many schools offer mentorship to guide project work, providing checkpoints to ensure a student’s project aligns with their identity, beliefs, and society’s needs. Yet, in an environment that does not encourage self-reflection or moral questioning, can young students truly know and question who they are on a frequent enough basis? Pick your favorite scientific journal, and you will find plenty of studies about how reflective practices such as meditation, self-examination, and journaling correlate with ethical maturity, longer-term satisfaction, and higher decision satisfaction.

Research brings validity to my worries, but I call on every reader to reflect on their experience. Many of us have seen how easily others can shape our aspirations at any stage, and it's no different for children. For example, when I was fourteen or fifteen, my dad steered me toward engineering because it seemed like the obvious, lucrative choice. Everyone assured me that this path fit my identity and promised success. I rarely questioned whether it was indeed my dream. I only one day said I wanted the thing, and the environment helped me achieve it, and it was not until I realized I never wanted it that I changed paths. Like me, some take the correct course while others regret following a set course for life.

How many adults in their 30s, 40s, or 50s eventually feel they were on autopilot—chasing goals they never truly desired? They may be successful and admired, but when the excitement fades, they often feel empty. Some try drastic changes, like flying to Peru for Ayahuasca, while others cling to new communities or beliefs in search of answers.

I do not claim that joining a school that stresses moral reflection will guarantee happiness. However, such an environment may encourage more thoughtful decision-making. When you regularly examine who you are and what you stand for, you can better judge the cost of your choices. You might also realize that reaching your goal should not come at the expense of your values.

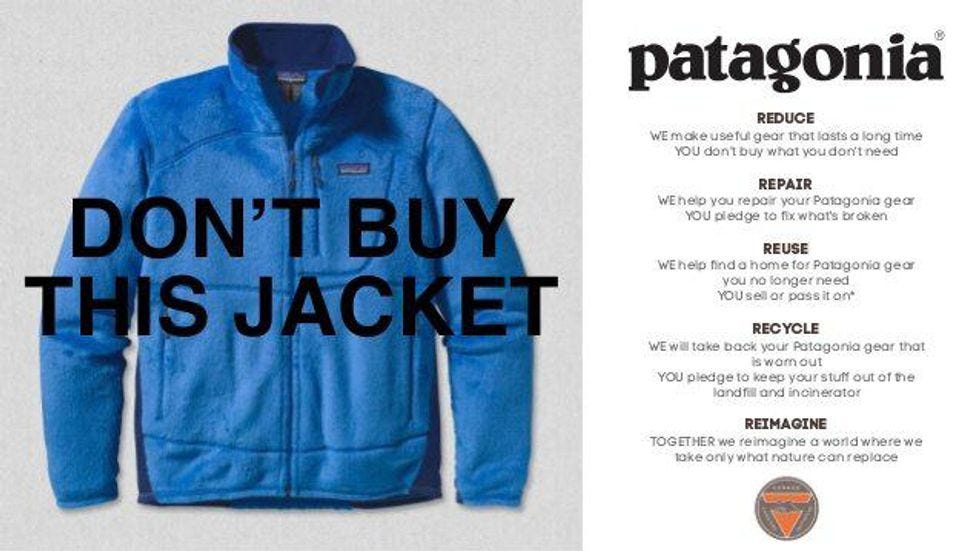

Consider the example of building a billion-dollar clothing brand. One path is to mimic Zara, with mass production that harms the environment and exploits workers. Another might follow Patagonia’s lead, focusing on environmental care, durable products, and shared global welfare. Both paths can lead to a billion-dollar company, but their moral footprints differ significantly. Same goal, different how. Can children in an outcome-focused setting like Zara's learn to see these differences?

The fact that many parents invest heavily in results-driven schools suggests that some value achievements over moral debate. Some parents may prefer a space without ethical discussions, viewing it superfluous or threatening. After all, once you acknowledge ideas such as that there is such thing as "right" and "wrong," you might have to admit that your path to success wasn’t entirely honorable. Could it be simpler, psychologically, to deny any moral lens? Is this worth doing if the repercussion is a life of outward success and inner dissatisfaction?

III.

Wall Street offers many examples of harsh work environments where people are treated like pawns and only rewarded when they boost someone else’s financial gain. Although many achieve wealth by their forties, they often suffer health problems, regret, and emotional scars from a life built purely on utility.

If an education system focuses only on outcomes, could it create a pipeline to success stories that lack ethical grounding—much like the school-to-prison pipeline in other contexts? Might we inadvertently nurture the next Adam Neumann, Martin Shkreli, or Elizabeth Holmes? I'm not one to say we are, but looking at the outcome-driven environments in which they thrived, can we confidently say we are not? The argument may seem speculative—until we recall real-world environments that promote similar values and the outcomes they produce. Sometimes, the evidence is right in front of us.

Not everyone values moral reflection or deeper fulfillment; some simply want to reach their goals. However, many recognize success can coexist with self-reflection, morality, and shared humanity. Which future should we wish for the next generation?

Nicolás, this is needed, urgent and excellent. Thank you thank you for raising these critical questions.